Pain: Is It All In Your Head?

Pure Sports Medicine

- 21 January, 2019

- Pain Management

- 4 min read

Warning: This post includes a graphic injury image that may upset some readers.

Sat between your ears is the most impressive bit of kit you own. Billions of neurones forming more connections than there are stars in the Milky Way, all packed into a protective case weighing about the same as a bowling ball. This incredible organ makes up the most important part of the central nervous system which creates our sense of reality through complex electro-chemical signals.

One fascinating attribute of the brain is how it manipulates sensory experiences based on different contexts. Take taste for example – your favourite glass of wine is more delicious tasting in a fine restaurant than it would be drunk from a plastic cup at home whilst watching bad TV. The food will probably taste better too, than if it was slapped on a plate by a suspicious looking chef in a budget café.

Pain is also a sensory experience manifested by the brain – the strongest weapon it can deploy when it wants to promote an action or a specific behaviour. But is pain accurate? The more something hurts means the more it is damaged, right?

What Controls Pain?

Many things influence a pain experience. Let’s assume that there is the same extent of soft tissue damage in each of the following two scenarios, how do you think the pain you feel will differ?

- You’re running late, rushing to work for a meeting. It’s crowded and you twist your ankle on a paving slab that’s sticking out. After falling over, you’re deeply embarrassed and angry at the council for their negligence. You feel like everyone around you is laughing, do you go to A&E? Will the boss fire you?

- You fall over and sprain your ankle whilst escaping from a burning building – you are back up in a flash completely unaware of any injury and manage to escape the danger.

The last scenario is an example of something called Stress Induced Hypoalgesia. Survival is key in this instance, as it is more important that you escape the fire than consider your ankle pain. The brain will override the pain sensation allowing you to escape danger without risking your life. Whilst the pain in scenario one is likely amplified by the surrounding environment. This can be termed Stress Induced Hyperalgesia and in some situations, it is possible, via this mechanism, to feel pain without any physical injury at all. My wife is a great example of this; she is a severe needle phobic, even a simple glimpse of someone receiving an injection on TV will give her pain as though she were receiving it herself. In a similar way; in her retirement, the famous dancer Dame Margot Fonteyn reported feeling pain in her arthritic feet upon seeing her ballet shoes. It is not unusual for persistent pain sufferers to report experiences like this as well.

Why Do People Experience Pain Differently?

Pain has always fascinated scientists and clinicians alike. Across the world, clinics are full of patients suffering with unexplained pains, which stem from seemingly innocuous injuries and persist well beyond the normal recovery timeframe. Yet at the same time there are stories of people sustaining serious injuries that they have no awareness off. Such as the story of Robert Kincaid, a World War II veteran who underwent a routine x-ray later in life, and discovered a bullet wedged in his neck. He had no idea that he had been shot over 60 years earlier.

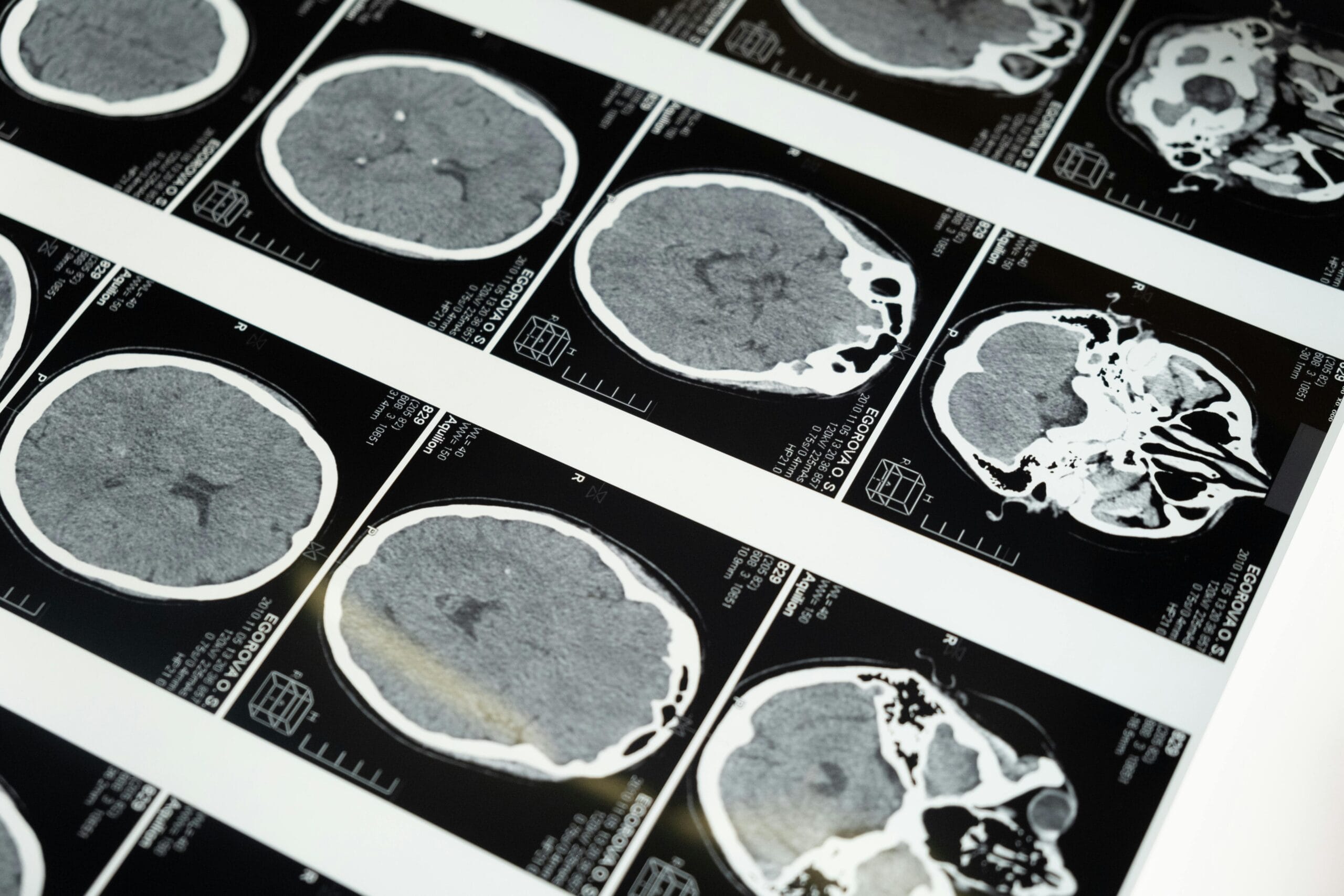

In the clinic, you often meet fascinating people and hear interesting pain stories. Phil is one example. A highly charismatic and talented amateur jockey, he came off a bicycle at great speed and hit a tree. He fractured his skull, sternum and sustained a complex spinal fracture, which was operated on shortly after the accident. He also has a bruised heart, spleen and other organs. He recalls;

“I thought I’d just got a cut to my head and pulled the muscles in my back. It was only really after the CT scan when they diagnosed me with the fractures that the pain and shock really kicked in.”

Much like our second scenario earlier, he was benefiting from stress-induced hypoalgesia until the moment he realised the extent of the damage. His recovery was outstanding, partly because of his confidence in his recovery, continual determination and lack of concern surrounding the injury. A few months later he was in the gym lifting heavy weights and is now back riding bikes and horses.

Compare that story to another patient – Nick who is a self-confessed anxious type. Nick experienced agonising low back pain and sciatica spontaneously one evening whilst he was stood in a queue for a nightclub. The paramedics had to give him gas and air en route to A&E and he can recall being told somewhere along his journey that he might need surgery and that worst case scenario – could end up in a wheelchair.

People like Nick often have pain that persists for a long time after it’s onset due to the ‘pain memory’ being firmly imprinted into the brains sensory network. It is well known that a high degree of stress and anxiety around the time of an injury is a bad predictor for recovery. Memories form better if they are associated with high levels of stress or anxiety. Even ones which don’t involve physical pain. For example, we have all experienced that flashbulb moment – you might remember exactly where you were and what you were doing the exact moment you heard that the twin towers came down.

Persistent pain for people like Nick is complex, and science is just starting to understand its multifactorial nature, including the influence of other psychosocial factors such as chronic stress, poor sleep and a lack of exercise. Most pain sufferers have a poor understanding of their condition. They often lack control over their pain and find it limits their ability to enjoy life. It can be a long road to recovery but one of the first steps in the right direction is to understand that hurt doesn’t always mean harm. Pain is rarely an accurate representation of true tissue damage and for pain sufferers, it is often a sign of tissue sensitivity and an overprotective nervous system trying to protect you from a perceived and often non-existent danger.

If you are currently affected by persistent pain, it is advised that you seek medical advice from a specialist Osteopath, Physiotherapist or Doctor, who will be able to help you to identify the factors causing your pain and help you in your recovery. Book an appointment today.

Advice

Over the last 20+ years our experts have helped more than 100,000 patients, but we don’t stop there. We also like to share our knowledge and insight to help people lead healthier lives, and here you will find our extensive library of advice on a variety of topics to help you do the same.

OUR ADVICE HUBS See all Advice Hubs