Female ACL Injury Risks: Anatomy, Hormones, and Prevention

Rebecca Christenson

Advanced Physiotherapy Practitioner

- 18 September, 2025

- Rehabilitation

- 10 min read

ACL injuries are one of the most pressing issues in women’s football. From England’s Lionesses Leah Williamson and Beth Mead to countless grassroots players, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears are threatening the long-term knee health of female players.

Why Are Elite Female Athletes Facing a Rise in ACL Injuries?

Female athletes are two to eight times more likely to suffer ACL injuries compared to their male counterparts. This disparity has sparked research across elite sports, particularly in football where popularity, intensity and physical demands of the sport have increased.

With women’s football on the rise, global organisations are investing in understanding and preventing these injuries. FIFA, for example, has funded a year-long research initiative into ACL injury risks in women, focusing on the role of hormonal fluctuations and biomechanics.

This comprehensive guide will explore the causes, symptoms, diagnosis, recovery, and cutting-edge prevention strategies for ACL injuries in female footballers. Whether you are playing at an elite level or enjoying weekly five-a-side, understanding these risks is essential.

At our London-based sports clinics, we are committed to transforming research into real-world injury prevention, so you can stay stronger, longer, and in the game you love.

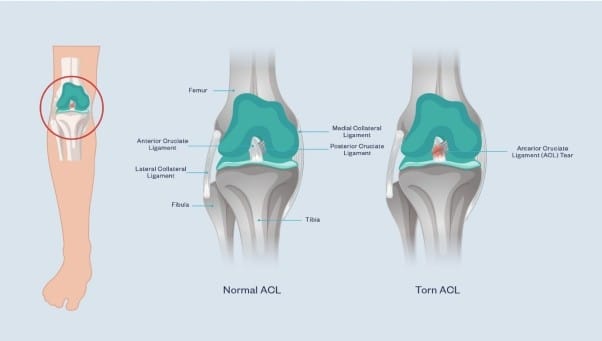

What Is an ACL Injury?

“The typical mechanism of injury we see in football is a fast deceleration and change of direction. We don’t tend to see ACL ruptures just from a hard tackle,” explains Rebecca Christenson, Advanced Practice Physiotherapist at Pure Sports Medicine.

ACL injury’s most commonly occur without contact – often when a player suddenly pivots, decelerates, or lands awkwardly.

Symptoms: How to Identify an ACL Injury

Recognising ACL injury symptoms early can make a significant difference in your recovery.

Common signs of an ACL injury:

- A sudden popping sound at the time of injury

- Rapid swelling within the first few hours

- A feeling that the knee is unstable

- Deep internal knee pain

You might be wondering, “what does an ACL injury feel like?” Most describe it as a deep pain inside the knee and that something has been torn. The injury makes movement difficult. It may feel like the knee has “given way” and it’s not uncommon to feel weakness or a lack of control in the joint.

“Patients tend to know they have torn something and will often report the knee feeling unstable. When the ACL is torn, it typically results in significant swelling due to the trauma within the joint,” comments Rebecca.

Why Are ACL Injuries So Common in Women’s Football?

More research is required, but currently some evidence points to a complex interplay of anatomical, hormonal, and neuromuscular factors that uniquely affect women, which are detailed below.

1. Biomechanical Factors

Contrary to popular belief, women do not have a wider pelvis than men. However, they do tend to have a greater Q angle—the angle formed between the quadriceps muscle and the patellar tendon. A larger Q angle can increase the likelihood of the knee collapsing inward, placing additional stress on the ACL. There is some evidence associating Q angles greater than 19 degrees with an elevated risk of ACL injury. However, current research suggests that ACL injuries are multifactorial, and there is no simple cause-and-effect relationship.

Women typically have smaller ACLs and greater joint laxity, which may reduce the ligament’s ability to withstand force. However, more research is needed as there is not an established link between ACL size and injury risk.

The posterior tibial slope is also steeper in many female athletes, increasing forward tibial translation during landings. Together, these anatomical features may place more stress on the ACL.

Muscle recruitment patterns matter too. Female athletes often rely more heavily on their quadriceps during landings, with less hamstring engagement. Female athletes have also been shown to have lower hip abductor strength per percentage of body weight and greater knee adduction during single leg landing compared to male athletes. This landing strategy, coupled with the lower contribution of the hamstrings will increase stress on the ACL during sport activity.

2. Hormonal Influences

Hormonal fluctuations across the menstrual cycle are increasingly recognised as a potential contributing factor to ACL injury and can affect ligament laxity and neuromuscular control.

A 2024 UK study by University College London, University of Bath, and St Mary’s University, found that muscle injuries in female players were six times more likely to occur in the days leading up to menstruation, coinciding with hormonal phases where oestrogen is high and progesterone is low – conditions that may make the ACL more vulnerable.

The ACL has oestrogen and relaxin receptors, and both hormones are also known to influence tissue laxity. While cycle tracking and training modifications around these phases are gaining popularity, hormone cycles are highly individual, and more research is needed.

Interestingly, some studies suggest oral contraceptives (OCPs) may help reduce hormonal fluctuations and lower injury risk and offer a protective effect against ACL injuries, though there is no official recommendation to prescribe OCPs solely for ACL injury prevention.

“The research being funded by FIFA is an important step in improving our understanding of ACL injury risk in female athletes. By identifying modifiable risk factors, the aim is to reduce the incidence of ACL injuries among women in sport,” adds Rebecca.

3. Neuromuscular Control

Until recently, most of what we knew about strength and injury prevention was based on research conducted almost exclusively on male athletes. The assumption that this data could be applied directly to women has proven problematic. Female players are often asked to perform at elite levels without the tailored support systems that their male counterparts receive—putting them at higher risk of both acute and overuse injuries.

Compared with men, women tend to have lower strength and power relative to body mass. While more women are now embracing strength training, the historical underrepresentation of women in resistance-based conditioning continues to have a knock-on effect on injury risk. It has led to reduced strength and slower reaction times, both of which can affect how the knee responds to rapid, multidirectional movements.

Although we cannot change certain anatomical risk factors; areas like strength, landing technique, postural control, and neuromuscular timing are modifiable – and this is where injury prevention programmes come in. The mechanics of how we move are important and can be addressed with the help of a Physiotherapist or Strength & Conditioning Coach.

“When we take patients through their end stage rehabilitation we will address risk factors in their movements – such as landing techniques and control,” explains Rebecca. “However, what would be great is if more female players were taking part in injury prevention programmes in their football clubs.”

4. Environmental & Social Factors

Many female teams train and compete on substandard pitches, which feature uneven surfaces, poorly maintained turf, or overly compact grounds that can increase the risk of injuries.

Secondly, most football boots are still designed based on male foot anatomy, with limited options tailored to female biomechanics. Unsurprisingly, 82% of women have reported discomfort when playing in standard boots. An ill-fitting boot not only affects comfort but also disrupts balance, traction, and joint loading, which may increase the likelihood of injury.

The Professional Footballers’ Association (PFA), Fifpro, Nike, and Leeds Beckett University are leading a three-year study to create scalable, evidence-based injury prevention strategies tailored to female footballers. Their goal is clear: make these programmes widely accessible, regardless of playing level, so that all women in football can benefit from effective injury reduction tools.

5. Infrastructure Challenges

Girls often enter adulthood with fewer cumulative hours of structured football training. This can affect motor control and movement efficiency. While early participation is increasing, more support is needed to retain girls in sport and provide the same developmental opportunities.

How to Assess an ACL Injury

If an ACL injury is suspected, it’s important to get it checked as soon as possible to ensure the best treatment pathway is taken and to prevent further damage to the knee.

To get a diagnosis, the process involves a thorough history taking, a combination of clinical tests and imaging techniques at one of our sports clinics.

Several hands-on assessments are commonly used to check the integrity of the ACL. The two most reliable are:

- Lachman Test: the gold standard when it comes to how to assess ACL injury. The clinician stabilises the thigh and gently pulls the shin forward. Excessive forward movement or a soft end feel suggests a torn ACL.

- Pivot Shift Test: this test assesses rotational instability in the knee, mimicking the sensation of “giving way” that many ACL-injured athletes report.

“The patient’s history is an important part of the diagnostic process,” adds Rebecca. “Suspicion of an ACL injury will be high if a patient reports a sudden deceleration or pivot that allows their knee to rotate in, and they feel something give or pop. If they report a lot of swelling, then this also indicates internal trauma in the knee.”

Other tests may also be performed to check for associated damage to the meniscus or collateral ligaments, which can be injured alongside the ACL.

While clinical tests are highly informative, they are often followed by imaging to confirm the diagnosis and assess the extent of the injury.

How is an ACL Injury Treated?

When it comes to ACL injury and treatment, there’s no one-size-fits-all approach. The right path depends on factors such as the severity of your injury, your level of physical activity, age, and personal goals.

A common question is: “Can ACL injuries heal on their own?” The answer is not straightforward. Some evidence suggests that about one-third of patients managed non-surgically show signs of ACL healing on MRI scans. Additionally, around 50% of people can return to sport and function well without surgery, even if the ligament has not fully healed. However, outcomes tend to be better when healing has occurred.

That said, even when the ACL does heal, it may not reattach in exactly the right position. This can affect its ability to stabilise the knee. For this reason, many surgeons are concerned about the potential for further knee damage if the ligament is not reconstructed.

So, What Next?

If you experience an ACL tear, it is important to have a thorough individual assessment to determine the most appropriate treatment pathway for your specific needs.

Preliminary research has shown promising outcomes using a bracing protocol to support ACL healing. However, further studies are needed before this method can be fully understood and implemented in our clinical practice

Non-surgical ACL injury treatment includes:

- Targeted Physiotherapy to strengthen the muscles around the knee, particularly the hamstrings and quadriceps, to compensate for lost ligament function

- Neuromuscular training to improve balance and movement control

- Bracing may be considered

- Massage therapy to address surrounding muscle tightness and swelling.

At Pure Sports Medicine, our expert Physiotherapists and Rehabilitation Specialists deliver personalised non-surgical recovery programmes for ACL injuries, guiding you through every stage—from swelling control to sport-specific retraining.

Many people who want to return to sports involving cutting and change in direction will choose to have a surgical reconstruction. However, it is important to recognise that this approach also requires a prolonged period of rehabilitation, comparable to non-operative management. In addition, having surgery does not guarantee a better outcome.

“An ACL injury is a significant challenge, both physically and psychologically. Rehabilitation is a long journey, and setbacks are common—regardless of whether you choose surgical or non-surgical management. But with the right guidance from an experienced physiotherapist, combined with commitment and consistency, recovery is absolutely possible.”

How Long Does it Take to Recover From an ACL Injury?

An ACL injury recovery time typically ranges from 12-18 months, depending on the extent of the injury, and the quality of rehabilitation.

At Pure Sports Medicine, we offer a comprehensive ACL rehabilitation pathway, combining strength and conditioning, strength testing, biomechanical analysis, and return-to-play protocols to support safe, confident recovery—whether you’ve had surgery or not.

The Science of Prevention

Prevention programmes, when implemented well, can make a substantial difference to injury risk. So, if you are playing regular sport, a prevention programme should be a part of your training.

The FIFA 11+ warm up programme, designed by FIFA Medical Assessment and Research Centre (F-MARC), has been shown to reduce sports-related injuries in up to one-third of young female athletes. Preseason training aimed at correcting high-risk landing mechanics has been shown to reduce ACL injury risk by 1.83 times in female athletes compared to those not participating in such programmes.

Evidence shows us that if you carry out a researched injury prevention programme 2-3 times per week, with good coaching, you can reduce the chance of ACL injury by 20-50%.

To get a personalised strengthening programme for you, it’s best to see a trained professional such as a Strength & Conditioning Coach.

Why Prevention and Education Matter More Than Ever

So, there you have it—the multi-layered reality behind why female footballers face a higher risk of ACL injuries. The potential causes are complex and multifactorial, ranging from biomechanics and hormonal fluctuations to equipment, training exposure, and the environments women play and train in. But understanding this complexity is the key to changing the future.

While the women’s game has come a long way, prevention and education remain our most powerful tools. We now know that ACL injury risk can be significantly reduced with the right combination of strength training, movement education, load management, and athlete-specific conditioning, but these strategies must be integrated early and consistently.

With organisations like FIFA, the PFA, Fifpro, Nike, and Leeds Beckett University investing in large-scale, female-focused research, we’re finally seeing the global sports community take ACL injuries seriously.

At Pure Sports Medicine, we’re proud to support female athletes at every stage. We understand that each ACL injury is unique, and so is every recovery. But no matter your starting point, you deserve care that’s targeted, personalised, and evidence informed.

Nothing should stop young women and girls picking up and enjoying the sport of football throughout their lives. Even if someone experiences an ACL injury, we are on hand to help you get back to your best and, most importantly, back on the pitch.

FAQs

1. Do ACL injuries heal on their own?

Yes, they can heal but it is not straight forward, and more research is needed. The question should perhaps be ‘can a healed ACL function sufficiently to stabilise the knee?’ At the moment, we do not have enough evidence to answer this. Even if the ligament does heal it may not reattachment in exact right position, which can affect the stability of the knee. But when healing does occur it associated with better outcomes. Bracing is a hot topic, but we need to understand more about if this can be used to facilitate healing.

2. Is an ACL a Soft Tissue Injury?

Yes. The ACL is a ligament, and ligaments fall under the category of soft tissue, along with muscles and tendons. Because of its role in knee stability, an ACL injury is one of the more serious soft tissue injuries and often involves additional structures like the meniscus.

3. Can an ACL Injury Cause Back Pain?

While an ACL injury does not directly cause back pain, it can lead to changes in how you move, which may place extra strain on your lower back. After an ACL tear, people often adapt their posture or walking pattern to protect the injured knee. Over time, these compensations can affect the alignment and loading of other joints, including the spine.

If back pain develops during your recovery, it is important to mention it to your physiotherapist. Addressing movement patterns early can help prevent secondary issues and support a more balanced rehabilitation.

4. How Do I Strengthen the Knee After an ACL Injury?

Strengthening the knee after an ACL injury involves a structured rehabilitation programme tailored to your stage of recovery and individual needs. Early on, the focus is on reducing swelling, restoring range of motion, and activating key muscles like the quadriceps and hamstrings. As recovery progresses, exercises become more targeted—working on strength, balance, and control around the knee, hip, and core.

Later stages of rehab include sport-specific drills and movement retraining, such as improving landing technique and agility. Working with a physiotherapist ensures that exercises are progressed safely and effectively, helping you build strength and confidence while reducing the risk of re-injury.

Advice

Over the last 20+ years our experts have helped more than 100,000 patients, but we don’t stop there. We also like to share our knowledge and insight to help people lead healthier lives, and here you will find our extensive library of advice on a variety of topics to help you do the same.

OUR ADVICE HUBS See all Advice Hubs