Common Lower Limb Injuries in Dance & Performing Arts

Lauren Fekete

Physiotherapist

- 19 November, 2024

- Dance & Performing Arts Medicine

- Lower Limb

- Podiatry

- 7 min read

According to research, up to 80% of dancers will have an injury that impacts their capacity to dance, with overuse accounting for the majority of injuries [1,2,3,4].

Due to immense physical and psychological demands within dance and the performing arts, injuries are both plentiful and multifactorial in nature.

Other genres of performing arts also suffer similarly high injury rates including over 50% of professional musicians and actors reporting injuries annually, whilst circus performers have been found to report about 7-9 injuries per 1000 performances [6,7,8,9,10].

Although some sectors within the dance and performing arts spheres have gradually begun incorporating injury prevention principles (including emphasising the importance of strength and conditioning, cross-training, and nutrition), extrinsic risk factors such as long rehearsal schedules resulting in inadequate rest and specialised footwear, such as pointe shoes, are not as easily altered.

To address the many aspects that can increase the risk of injury for dancers and performers, we must first delve into common areas of injury.

Performers and Lower Limb Injuries

The lower limb is one of the most common areas where dancers and performers report injuries [1,2,3,4,5], the foot and ankle in particular are at increased risk of injury due to unique positions such as en pointe, which places a significant amount of stress to the toes and ball of the foot.

Common Foot & Ankle Injuries

1. Ankle Impingement (lateral, medial, posterior, anterior)

When clinicians talk about ‘impingement’, we often mean that two bony surfaces are a bit too close together in certain movements, which can result in the surrounding soft tissue being ‘crowded’, or ‘irritated.’ This can also occur functionally rather than structurally due to muscle imbalance and biomechanical abnormalities. In the ankle, there are multiple places this can occur:

- Anterior (or in the front of the ankle), results in a ‘pinching’ sensation or ‘block’ in movements in which the knee is bent and ankle flexed, like plié.

- Lateral (on the outside of the ankle), can often cause pain in movements like eversion/ ‘winging’ the foot). Excessive ankle ‘pronation’ at the inside of the ankle (which can resemble arch ‘collapse’) can result in impingement on the outside of the ankle.

- Medial (on the inside of the ankle) usually occurs after an inversion sprain/ ‘rolling over’ on the ankle, resulting in contact between the two bony surfaces of the medial malleolus and calcaneus (heel bone).

- Posterior (at the back of the ankle), commonly becomes symptomatic with repetitive pointing of the foot or pushing off and can arise from benign ‘extra’ bony prominences around this area like an os trigonom or a Stieda process).

2. Tendinopathy

Tendinopathy, often referred to as ‘tendinitis’ when acute) typically occurs when tendons (which attach muscle to bone), are undergoing too much load (or a big change in load) and do not have the physiological capacity to cope.

Sometimes this can be due to the attached muscle being ‘weak’ and transmitting excessive force to the tendon, and other times this can occur from suboptimal loading patterns (such as excessive pronation or supination of the foot in standing and landing, which can result from weakness higher up the chain).

Although tendinopathy can occur in any tendon in the body, commonly in dancers and performing artists, the ones most affected in the foot tend to be:

- The big toe flexor tendon (also known as the flexor hallucis longus, or FHL for short)

- A medial ankle tendon known as the tibialis posterior (which can become overloaded when ‘sickling’ or ‘over-winging’ the foot or when loading with ‘collapsed arches’)

- Lateral ankle tendons of the peroneal muscles (which help evert/‘wing’ the foot)

- Achilles tendon which assists the foot to point, or plantarflex.

3. Hallux rigidus and hallux valgus (bunion)

The big toe is extremely important for performers who dance on the balls of their feet (ballet, contemporary, ballroom, Argentine tango, etc.). Sometimes due to overloading the big toe joint (also referred to as the 1st metatarsophalangeal, or 1st MTP joint for short) can become stiff or ‘rigid’ and no longer be able to achieve its full range of motion, resulting in ‘knock on’ effects of the body trying to move its weight over the side of the foot.

Narrow or tight shoe wear that taper too much such as pointe, character, or ballroom/tango heels can also cause crowding of the metatarsals which results in a ‘tilting’ of the big toe inwards toward the other toes and accompanying joint responsively largening.

4. Fractures (stress fracture and traumatic)

Continuous repetitive loading and impact of the bones in the foot and ankle, often paired with lack of rest, under fuelling, and altered biomechanics, can result in bony stress responses which can progress to stress fractures if not recognised early.

Performers can also acquire traumatic fractures of the base of the 5th metatarsal (sometimes known as a ‘dancer’s fracture’), and tip of the lateral malleolus (end of the fibula) by rolling the ankle when landing from a jump, fatigued, or due to chronic instability.

Performers that dance primarily en pointe, demi pointe, or in high heels (such as ballet, ballroom, Flamenco, and Argentine tango dancers) are exposed to higher load through their metatarsal heads and more likely to undergo repeated stress and potential bony overload in these areas.

Other Common Lower Limb Injuries

1. Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome (MTSS)

Also known as ‘shin splints’, MTSS can result in a feeling of achiness and tenderness along the inside of the shin, usually at the region between the soft tissue and shin (tibia).

Symptoms can increase at onset, during, or after activity that involves repetitive impact or loading (such as jumping) and often when there is a sudden increase in these activities without adequate rest or preparation.

Usually, the symptomatic ‘region’ is over 5 cm in length, if more localised than this and/or accompanied by any bony deformity, our index of suspicion for stress fracture would be higher. Irish step, contemporary, and ballet dancers are more likely to experience this injury.

2. Meniscal tears

The meniscii (both medial and lateral) are fibrocartilaginous, donut-shaped tissues in the knee that cushion and assist with shock absorption.

Performing art forms that require a lot of twisting or deep squatting such as break dancing, contemporary, and some forms of Indian dance such as bhangra, can be more at risk for meniscal injuries.

Often times performers feel a deep achiness in the inside or outside of the knee, there can be ‘locking’ or ‘clicking’ and swelling associated, and there is usually tenderness around the joint line as well as pain or difficulty in a fully squatted position.

3. Patellar tendinopathy

The patellar tendon connects the kneecap (patella) to the tibia (shin) and helps anchor the thigh muscles (quadriceps).

Artists who tend to do a lot of jumping (such as ballet, contemporary, Irish step dancers, bhangra dancers) without adequate quadriceps strength or poor landing technique, can expose the tendon to loads it cannot handle causing pain in the area where your reflexes usually get tested.

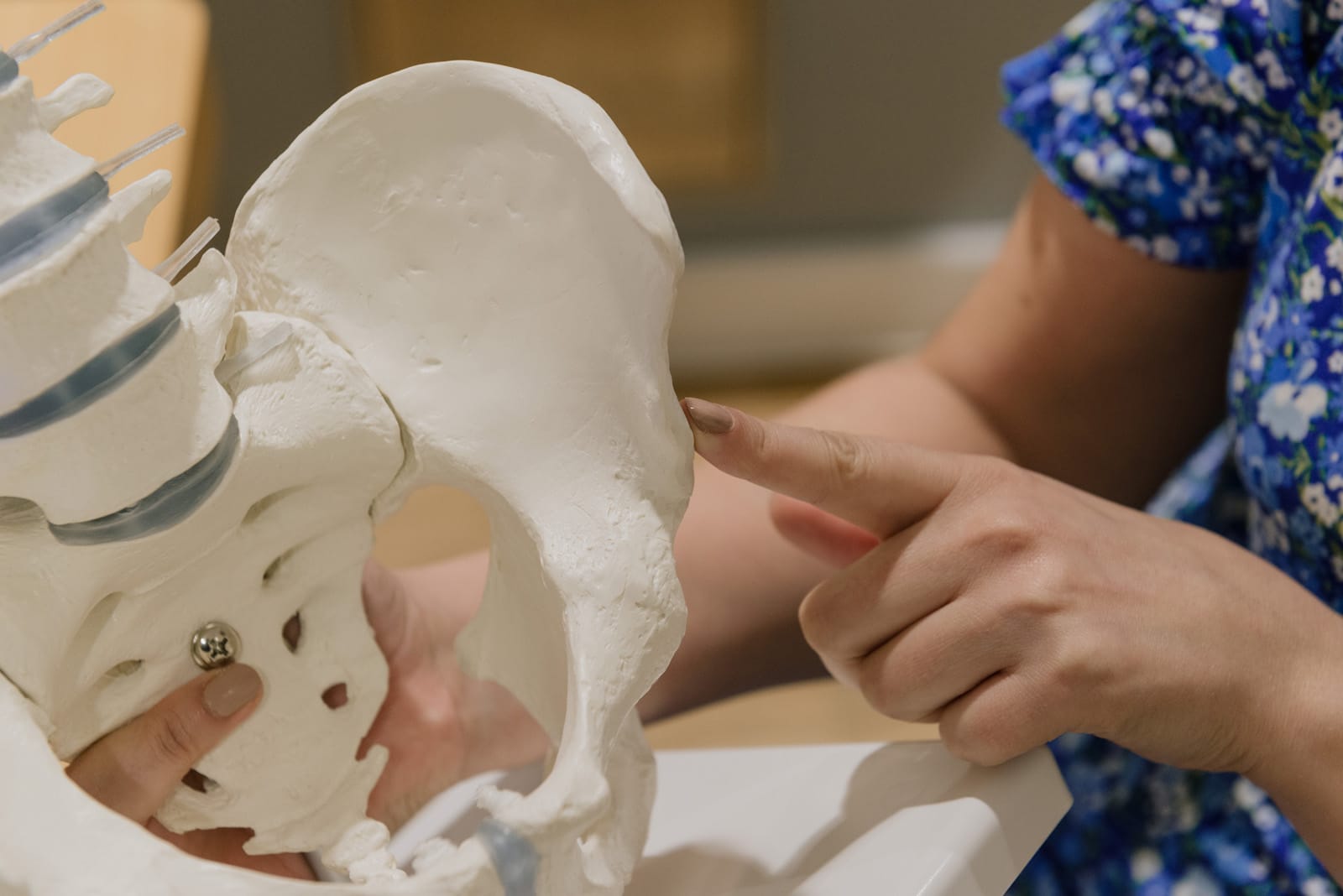

4. Hip Dysplasia

Now gaining more recognition as a driver of hip symptoms, dysplasia refers to a collection of structural factors that result in the socket of the hip joint (the acetabulum) being too shallow or not adequately covering the ball of the joint (the femoral head). This creates symptoms such as feelings of instability (which can occur in any direction of motion), pain, and ‘pinching’. Sometimes this is identified in infancy.

5. Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI)

FAI can be driven by underlying hip dysplasia, but can also have other structural causes such as ‘Cam deformity’ (when the head of the femur has some additional bony prominences) or ‘Pincer deformity’ (when the socket/’acetabulum’ lips over the head of the femur) causing a block of full hip range of motion.

Anterior ‘impingement’ (sometimes accompanied by hip flexor tendinopathy and weakness), can also result from functional causes such as tight gluteal muscles resulting in a ‘pinching’ sensation at the front of the hip. Often dance and art forms that require a high range of hip motion like ballet, contemporary, jazz, circus, and figure skating, are more at risk.

Prevention tips

Overall, many of the issues above can be prevented or resolved with initial reduction to the load on the tissue in question through rest (temporary footwear alteration, reduction or modification in specific classes or steps, etc.) increasing the capacity and resilience of the tissue (through strengthening, nutritional fuelling, etc.), and optimising biomechanical loading patterns through consultation with a physiotherapist.

Appropriate warm-up, cool down, nutrition, hydration, sleep, and addressing any mental health concerns, are also important factors that can reduce the risk of injury.

Fractures and bony stress responses often need a longer period of offloading through crutches and/or a boot, so make sure to report symptoms like localised bony pain, pain that causes difficulty weight-bearing, increased pain after jumping or impact, and night pain early to avoid catching these too late!

As with all injuries that involve bony overload or stress responses, it is crucial to ensure adequate nutrition to fuel your body, rest and recovery, so that your body can cope with required demands in load. Some signs that the balance between activity and rest are not at equilibrium include increased fatigue, low mood/irritability, higher frequency of injury, cessation of menstruation, and decline in performance. If you are experiencing any of these symptoms, speak to a specialist as these can be an indication of RED-S (Relative Energy Deficiency Syndrome).

References:

- N. Allen, A. Nevill, J. Brooks, Y. Koutedakis, M. Wyon. Ballet injuries: injury incidence and severity over 1 year. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther., 42 (2012), pp. 781-790

- C.L. Ekegren, R. Quested, A. Brodrick. Injuries in pre-professional ballet dancers: Incidence, characteristics and consequences. J. Sci. Med. Sport, 17 (2014), pp. 271-275

- T.O. Smith, L. Davies, A. de Medici, A. Hakim, F. Haddad, A. Macgregor. Prevalence and profile of musculoskeletal injuries in ballet dancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys. Ther. Sport, 19 (2016), pp. 50-56

- Diana P A M van Winden, Rogier M Van Rijn, Angelo Richardson, Geert J P Savelsbergh, Raôul R D Oudejans, Janine H Stubbe – Detailed injury epidemiology in contemporary dance: a 1-year prospective study of 134 students: BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2019;5:e000453.

- Kauther, Max & Wedemeyer, Christian & Wegner, Alexander & Kauther, Kai & Knoch, Marius. (2009). Breakdance Injuries and Overuse Syndromes in Amateurs and Professionals. The American journal of sports medicine. 37. 797-802. 10.1177/0363546508328120.

- Ackermann B, Driscoll T, Kenny DT. Musculoskeletal pain and injury in professional orchestral musicians in Australia. Medical Problems of Performing Artists. 2012;27(4):181

- Evans RW, Evans RI, Carvajal S. Survey of injuries among West End performers. Occup Environ Med. 1998 Sep;55(9):585-93. doi: 10.1136/oem.55.9.585. PMID: 9861179; PMCID: PMC1757638.

- Shrier Ian, Meeuwisse Willem H., Matheson Gordon O., Wingfield Kristin, Steele Russell J., Prince François, Hanley James, Montanaro Michael. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 6. Vol. 37. SAGE Publications; Injury patterns and injury rates in the Circus arts: An analysis of 5 years of data from Cirque du Soleil; pp. 1143–1149.

- Musculoskeletal injury profile of Circus artists: A systematic review of the literature. Wolfenden HEG, Angioi M. Mar 1; 2017 Medical Problems of Performing Artists. 32(1):51–59. doi: 10.21091/mppa.2017.1008. doi: 10.21091/mppa.2017.1008.

- Bolling Caroline, Mellette Jay, Pasman H Roeline, van Mechelen Willem, Verhagen Evert. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine. 1. Vol. 5. BMJ; From the safety net to the injury prevention web: Applying systems thinking to unravel injury prevention challenges and opportunities in Cirque du Soleil; p. e000492.

Advice

Over the last 20+ years our experts have helped more than 100,000 patients, but we don’t stop there. We also like to share our knowledge and insight to help people lead healthier lives, and here you will find our extensive library of advice on a variety of topics to help you do the same.

OUR ADVICE HUBS See all Advice Hubs